| The Case That Shook the Empire: One Man’s Fight for the Truth about the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre by Raghu Palat and Pushpa Palat, Bloomsbury India; 1st edition (August 23, 2019), 162 pages |

Who in their right mind would think that an Indian would get justice in the British legal system.? Between a person responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and a person arguing against the atrocities, whom would the so-called British legal system side with? Would the British system turn a blind eye to one of their own who had committed an unforgivable crime?

The answer is obvious now, as it was in 1924.

This book is about a defamation case filed by Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab during Jallianwala Bagh, against Chettur Sankaran Nair, a former Member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council. The trial lasted five-and-a-half weeks in London. There was nothing that indicated that this would be a fair trial. The judge was a racist who saw nothing wrong in Jallianwala Bagh, and the jury agreed with him.

English juries always sided with their own, even when they were murderers. The narrative that O’Dwyer’s actions saved the empire found acceptance. The media was no different from the legal system. London Times applauded the decision, stating that it was a decisive verdict and an assertion of the will of the English people to protect India.

The person who was dragged into the court by Michael O’Dwyer was Chettur Sankaran Nair, a former Member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, a former President of the Indian National Congress, and a retired Judge of the Madras High Court. Edwin Montagu, Secretary of State for India, described Nair “as an impossible person… He shouts at the top of his voice and refuses to listen to anything when one argues, and is absolutely uncompromising.” Also, as a Nair, he did not believe in Gandhi’s non-violence. Warriors by nature, Nairs were taught to retaliate when attacked. “I draw the line when asked to turn the other cheek to my enemy. If someone were to smite me on my cheek, I would chop his head off,” Nair once said.

There is more to like about him. He did not believe in Gandhi’s cuckoo plan for Khilafat, which he thought was impractical. And he was absolutely right, as that plan was purely for Gandhi’s ascendance into leadership than helping anyone. The Arabs or Egyptians did not want to be ruled by a Turkish Caliph. Come to think of it, even the Turks did not wish to a caliph. They were the ones who got rid of him and converted to a secular democracy. The Ottoman Empire was broken up, and some of the lands were under French control. There was no way a few petitions would cause France and Britain to sit and undo the damage they did. None of this mattered to Gandhi. He went so far as to suggest that Indian swaraj activity could be postponed if Khilafat ask could be advanced. Thus from a Swaraj, which meant self-rule for India, it got converted overnight to support an imaginary Caliphate in faraway Turkey.

Mr. Nair’s sharp personality is revealed through various anecdotes. Once Lady O’Dwyer was annoyed by Mr. Nair’s reaction to her pet. “Nair rudely and rather cruelly replied that this was because, while the English were nearer to dogs in their evolution, Indians had in their 5,000-year history moved further away.” Directly quoted individual voices are the yeast that allows history to rise. When he resigned from the Viceroy’s council, he was asked to suggest a replacement. He pointed to the turbaned, red- and gold-liveried peon standing ramrod straight by the giant doorway. His reasoning is, “He is tall. He is handsome. He wears his livery well and he will say yes to whatever you say. Altogether he will make an ideal Member of Council.”

Despite all this, he believed that an Indian could get an impartial hearing at an English court.

Michael O’Dwyer was everything you would expect from a British overlord. He followed the Macaulay doctrine of contempt for Indian culture and constant reiteration of Western superiority. He believed that God had ordained Great Britain to govern the world. He also believed that British authority would be weakened if higher posts were given to Indians. He was intolerant of the growing wave of nationalism in India. He believed that India was won by the sword and must forever be preserved by force. On self-government, he proclaimed,” ‘India would not be fit for self-government much before doomsday.” Chettur Sankaran Nair was born in 1857, the year of the First War of Independence. Michael O’Dwyer and Reginald Dyer did everything to prevent anything like 1857 from re-occurring.

The book gives context to Jallianwala Bagh; it was not violence in isolation. We often speak of how Indian soldiers were all around the world during World War I. More than one million Indian soldiers were deployed during World War I, serving in the Indian Army as part of Britain’s imperial war effort. These men fought in France and Belgium, Egypt and East Africa, Gallipoli, Palestine, and Mesopotamia. What is not mentioned is how they were recruited. It’s not like a Punjabi farmer felt a sudden urge to go to Mesopotamia to defend his oppressor.

On failing to meet the recruitment targets, O’Dwyer took it upon himself to meet the goals and deployed new techniques. He did that by battering away at the darkest corners of people’s souls.

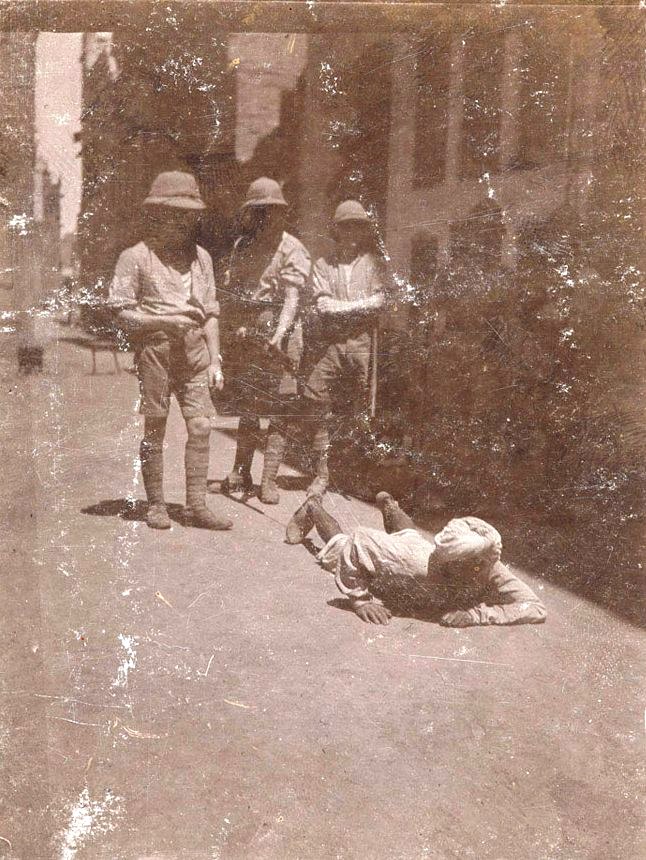

The committee also recorded men being captured forcibly and marched off for enlistment. Raids took place at night, and men were forcibly seized and removed. Their hands were tied together, and they were stripped in the presence of their families and made to bend over thorns when they were whipped. Additionally, women were stripped naked and made to sit on bramble bushes and thorn bushes in the hot sun until their men who had been hiding agreed to be recruited. In some instances, the women were made to sit with bramble between their legs overnight. Old men, too, had inhuman punishment meted out to them – they were made to sit ‘bare buttocks’ on thorns to force their sons to enlist.

Right now, we all know about what happened at Jallianwala Bagh. It’s mentioned in our history books, and many movies have depicted it. However, it was not so in 1924. Due to the draconian press rules, the atrocities in Punjab were not known around the world.

The book argues that there were some positive outcomes even though he lost the case. The court case between Nair and Michael O’Dwyer resulted in the whole world knowing about British atrocities (for which not a single British Prime Minister has apologized). It boosted the nationalist cause and a case of an Indian role in the administration of India(What an idea). No surprise on who did not send a note of encouragement or sympathy to this case – the Congress. For his efforts, there is a plaque honoring Sir Nair in the museum at Jallianwala Bagh, just outside the Golden Temple.

The book is short (162 pages). The author duo has written it in a vivid accessible style, which is how history books should be written. Together with a strong opening, setting the events of 1919 in their historical place, the reader is left with a history of British rule in Punjab from the Anglo-Afghan wars to the time of Jallianwala Bagh. Previously, I heard about Chettur Sankaran Nair from Maddy’s blog, but this book was a more detailed introduction.