Pratibha Patil, the virtual unknown, whom Sonia Gandhi picked up as the candidate for the President of India just to shut up Prakash Karat has established an albatross-neck relationship with the Congress Party. Her blame on the origins of the purdah system on Mughal invaders has created a new job position in the party for a Shane Warne level spin master. This statement by a candidate of a party which has been trying to white wash Indian history for the past half a century has upset all the secular fundamentalists.

The ultimate secular cuss word was used – pro-RSS. Her views were found to be similar to those of Hindu fanatics. Clueless newspapers like Deepika (Malayalam) said that Ms. Patil should not have made irresponsible statements (statements which affect vote bank) and provided the convincing argument that even the Congress spokesman disagreed with her, while in fact the Congress spokesman Param Navdeep said that it was an established fact that women were a target of aggression during the Mughal rule.

Eminent historians were immediately called into action by beaming the bat signal into the night sky.

Nandita Prasad Sahai, who teaches a course on the gender history of medieval India in JNU, says that there is

no consensus amongst historians about the precise period when purdah originated in Indian society.

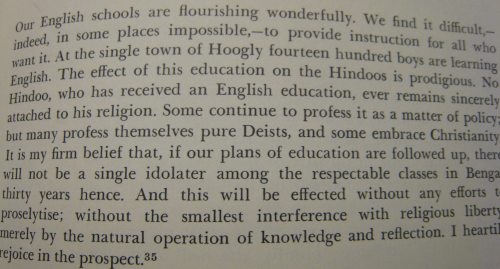

“Historian Kegan Paul traces the practice of the custom back to the Vedic period. And anthropologist Patricia Jeffrey says that seclusion and veiling of women was not unknown before the Muslim invasion. It appears that a social ideal recommending women to remain in seclusion to mark their complete loyalty towards their husband already existed,” she says.

“Most historians consider the Muslim invasion as a watershed when purdah is said to have become more widespread as a defensive reaction in troubled times among the Rajput royalty trying to protect their women. In fact, the case is unproven in the absence of statistical material that could establish a change in the extent of the practice of purdah . It seems plausible, however, that the practice became more widespread amongst the Rajput royalty in trying to imitate the custom of the new ruling classes,” says Sahai. [Experts lift veil off purdah origin]

Trying to push it back to the Vedic period is a nice JNU trick, but then facts disagree.

Some months ago, I recall a North Indian lady talking about the cultural differences she experienced when in South India. Visiting relatives posted in Kerala, she made a pilgrimage to the famed Shri Krishna shrine in Guruvayur. Upon entering the temple she devoutly covered her head — only to be sternly reprimanded by a priest who told her that this was against Hindu conventions.

The temple guardians at Guruvayur were quite right. I don’t know how many readers would have stepped into the National Museum in Delhi (sadly ignored by most visitors to the capital). The wealth of treasures in the museum is so great that it has actually spilled out into the lobby. One of the first pieces of sculpture you can see — before coming even to the ticket office — is a marvellous statue of the goddess Saraswati, from the Chauhan period as I recall.

The goddess of wisdom is portrayed without any covering on her head. So are depictions from thousands of years of Indian history, from the dawn of civilisation on the banks of the Sindhu through the Mauryas, the Guptas, and other dynasties. But as time passes — and you enter the galleries showing Rajput miniatures from later periods — the veil makes its appearance, until even Adishakti Parvati has her face partly covered.[The debate over Muslim separatism in the US]

While the Mughal era started in the 16th century, the Muslim invasion started much earlier with the invasion by Mahmud of Ghazni against the Rajput kingdoms and rich Hindu temples like Somnath, Varanasi and Dwaraka in the late 9th century. In the last quarter of the 12th century, Muhammad of Ghor established the Delhi Sultanate and sometimes the word Mughal rule is used incorrectly in a broader sense to include the Turkish and Afghan rulers as well.

One more attempt was made to push the date of the purdah system to pre-Muslim era by Vasha Joshi of Institute of Rajasthan Studies who suggested that the veil was prevalent in Rajasthan during the 11th century, much before the Delhi Sultanate. This remark was based on the existence of separate quarters for women called the jenani deorhi in medieval Chittorgarh fort which in no way implies the existence of the purdah system.

The Gandhara sculptures show women with band like head gear, but even that cannot be called the veil. Face covering was completely absent in India till the 11 -12th century and they are not present in the Ajanta paintings. Slowly the head covering starts appearing with the arrival of Muslims with a 1250-1275 book in Jaisalmer showing a woman covering the back of the head using the sari.

Pratibha Patil did nothing wrong, but stated a historical truth. Her only mistake was that she picked the wrong community to blame. Instead, if she had blamed the caste system or denounced Brahmins, it would have been accepted without debate that she was the person with the perfect secular credentials to be the President of India.